Case Study: Learning Through Emulation (Version 2.0)

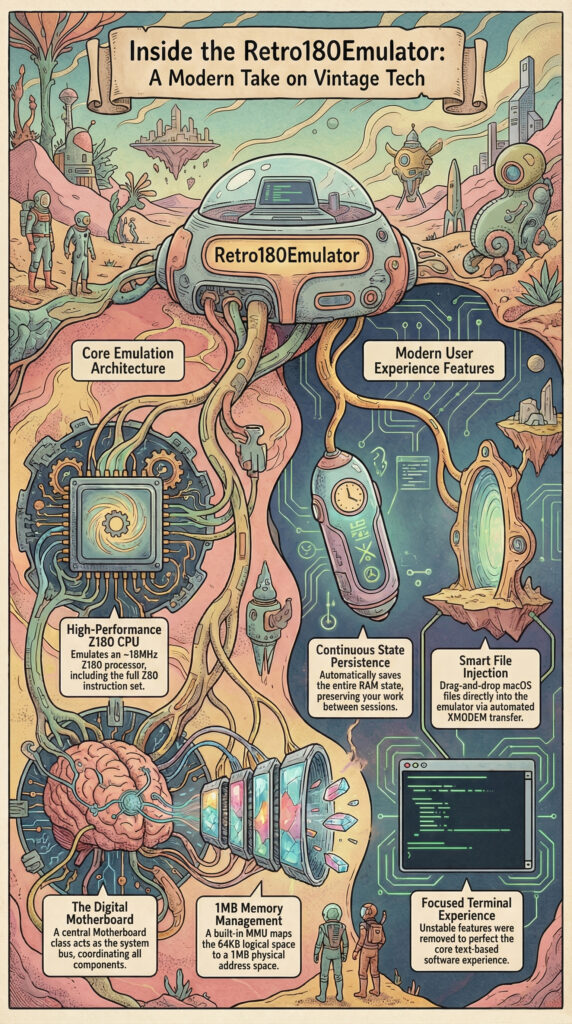

In this post, we are stepping away from theoretical diagrams to look at how a microprocessor system functions in practice. To understand how hardware and software work together to create a functional computer, let’s explore the updated Retro180Emulator. This project serves as our primary case study because it strikes a balance between architectural accuracy and modern software design, specifically targeting the SC126 Z180 Motherboard architecture to run the RomWBW operating system.

1. Architectural Philosophy: The Layered Approach

When designing an emulator for educational purposes, keeping things organized is key. The Retro180Emulator utilizes a layered architecture that distinctly separates the core hardware simulation from the user presentation layer.

The system centers around a Motherboard class, which acts as the system bus to coordinate communication between the CPU, Memory, and I/O subsystems. This design creates a clear boundary between the “backend” (simulation logic) and the “frontend” (SwiftUI Interface), allowing us to inspect the system state without risking unintended side effects in the simulation logic.

2. The Central Processing Unit (Z180)

At the heart of our virtual machine sits the Z180CPU. Unlike a standard Z80, the Z180 is a superset architecture that includes built-in peripherals and extended instructions.

Execution and Performance

The emulator implements the full Z80 instruction set plus Z180 extensions, including the hardware multiply (MLT) instruction. The emulator prioritizes utility over cycle-perfect precision. It utilizes a burst-cycle loop, executing approximately 5,000 instructions per UI frame to simulate a snappy real-time clock speed of roughly 18MHz.

3. The Memory Management Unit (MMU)

One of the most distinct upgrades of the Z180 over the Z80 is its built-in MMU, handled here by the Z180MMU class. While the standard Z80 is limited to a 16-bit logical address space (64KB), the Z180 extends this to a 20-bit physical address space (1MB).

The emulator replicates the hardware logic required to translate logical addresses to physical addresses using three specific registers:

- CBAR (Common/Bank Area Register)

- BBR (Bank Base Register)

- CBR (Common Base Register)

This banking logic is essential for running advanced 8-bit operating systems like RomWBW and MP/M.

4. State Persistence and Reliability

In the previous iteration of this system (Version 1.0), we utilized a stateless model. However, to better represent the behavior of a physical workstation, Version 2.0 introduces Continuous Persistence.

The system now serializes the entire 512KB RAM state into a binary file (`ram.bin`) located in the user’s documents. This process triggers automatically every 30 seconds and instantaneously upon application backgrounding or termination. This ensures that the operating system state and the contents of the RAM disk (Drive A:) are preserved between sessions, solving the volatility issues often found in stateless emulation.

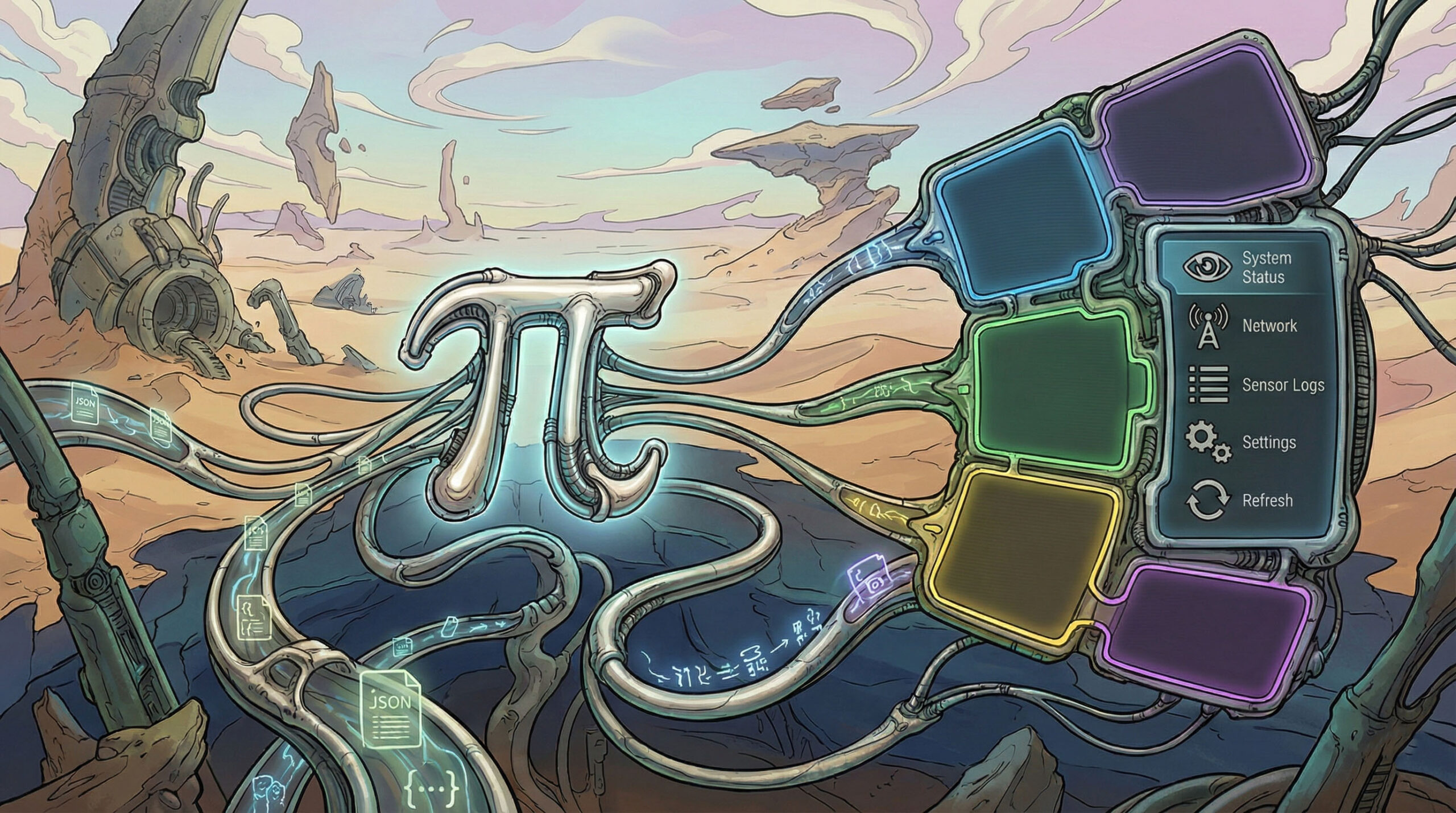

5. I/O Subsystem and “Smart Injection”

The emulator’s I/O Dispatcher supports the dynamic relocation of internal registers (typically to 0x00, 0x40, or 0xC0), which is a critical requirement for BIOS compatibility.

Interoperability: The “Smart Injection” Workflow

A major hurdle in vintage emulation is moving data from the host to the guest. Version 2.0 solves this with an automated “Smart Injection” workflow. When a user selects a file from the macOS host, the emulator acts as a “Macro” typist. It automatically injects the CP/M command B:XM R into the console input stream and initiates an internal XMODEM transfer, piping data directly to the emulated ASCI serial port. This demonstrates how modern software automation can bridge architectural gaps in legacy systems.

6. Strategic Deprecation and Focus

An important lesson in engineering is knowing what to remove. In the pivot to the SC126 architecture, specific features found in Version 1.0 were deprecated to reduce code bloat and improve timing stability.

Specifically, the SPI-based SD Card emulation and the SP0256 Speech Synthesis chip have been removed. While technically interesting, these features detracted from the stability of the core terminal experience. The project is now laser-focused on the visual and computational accuracy of the text-based interface, with future roadmap items targeting visual aesthetics, such as CRT shaders.

Conclusion

By studying the updated Retro180Emulator, we can see that computer architecture is not just about raw silicon; it is about the logical contracts between subsystems and the user experience. Through the Z180’s banking mechanisms, the persistence of memory states, and streamlined I/O routing, we see a complete, functional model of computation designed for stability and education.