View the code on Github

Case Study: Pedagogy Through Emulation

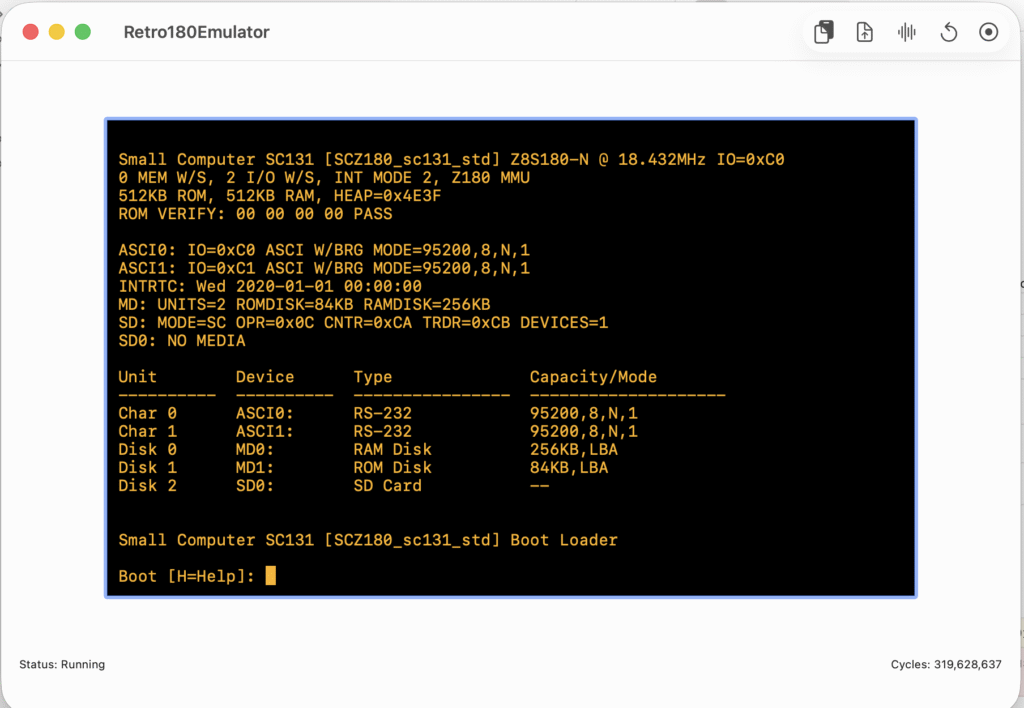

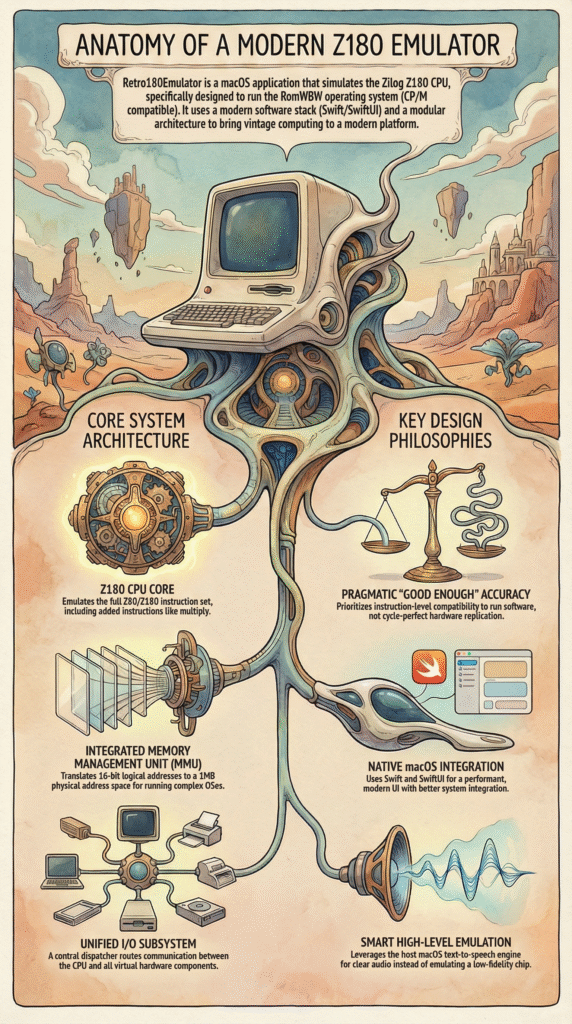

In this post, we move beyond theoretical diagrams to examine the practical implementation of a microprocessor system. To understand how hardware and software commingle to create a functional computer, we will analyze the Retro180Emulator, a project designed to emulate the Zilog Z180 microprocessor architecture on macOS.

This project balances architectural accuracy with modern software design patterns. Specifically, it simulates the SC131 pocket-sized computer architecture, targeting instruction-set compatibility sufficient to run the RomWBW operating system.

1. Architectural Philosophy: The Layered Approach

When designing an emulator for educational purposes, separation of concerns is paramount. The Retro180Emulator utilizes a layered architecture that isolates the core hardware simulation from the user presentation layer.

The system is centered around a Motherboard class, which acts as the integration point simulating the bus and clock. This design choice creates a distinct boundary between the “backend” (CPU, MMU, I/O) and the “frontend” (User Interface), allowing us to inspect the system state without altering the simulation logic.

2. The Central Processing Unit (Z180)

At the heart of our virtual machine is the Z180CPU. Unlike a standard Z80, the Z180 is a superset architecture that includes built-in peripherals and extended instructions.

Register State and Execution

The emulator implements the full Z80/Z180 register sets, including the main registers (AF, BC, DE, HL), alternate registers, and system registers like the Stack Pointer (SP) and Program Counter (PC). The execution logic follows the classic Fetch-Decode-Execute cycle implemented in a step() function.

For our purposes, note that the emulator avoids the complexity of Just-In-Time (JIT) compilation. Instead, it uses a switch-case interpreter. Given that modern host CPUs operate at 3GHz+, emulating a sub-20MHz Z180 via a naive interpreter provides sufficient performance while maintaining code readability and ease of debugging.

Interrupt Handling

A critical concept in architecture is how the CPU handles asynchronous events. The emulator supports Z80 interrupt modes 0, 1, and 2. Before every instruction cycle, the system checks for maskable interrupts via checkInterrupts() if the Interrupt Flip-Flop (IFF1) is enabled. This demonstrates the continuous polling mechanism required in non-threaded hardware simulation.

3. The Memory Management Unit (MMU)

Perhaps the most distinct feature of the Z180 over the Z80 is its built-in MMU, which we examine via the Z180MMU class. While the Z80 is limited to a 16-bit logical address space (64KB), the Z180 extends this to a 20-bit physical address space (1MB).

The emulator replicates the hardware logic required to translate logical addresses to physical addresses using three specific registers:

- CBAR (Common/Bank Area Register)

- BBR (Bank Base Register)

- CBR (Common Base Register)

This banking logic is essential for running advanced 8-bit operating systems. It allows the emulator to support the standard SC131 memory map, which places ROM in the lower 512KB (0x00000 – 0x7FFFF) and RAM in the upper 512KB (0x80000 – 0xFFFFF). Without this authentic MMU emulation, running RomWBW or CP/M Plus would be impossible.

4. I/O Subsystem and Dispatching

In our implementation, the Z180IODispatcher manages the I/O address space. A sophisticated feature of the Z180 is the ability to relocate its internal registers (such as the MMU and DMA registers) to different offsets in the I/O map.

The emulator handles this by intercepting reads and writes to a relocatable 64-byte window. This dynamic dispatch allows the software to support BIOS versions that move internal registers to high memory (e.g., 0xC0) to free up the zero-page for other peripherals.

High-Level Emulation (HLE) vs. Cycle Accuracy

A key lesson in this project is knowing when to abstract. The system includes a text-to-speech engine mapped to Port 0x50. Rather than strictly emulating the vintage SP0256-AL2 chip, which yields robotic, low-fidelity audio, the emulator uses High-Level Emulation (HLE).

When the emulator detects a write to Port 0x50 ending in a Carriage Return, it triggers the macOS AVSpeechSynthesizer. This creates a hybrid architecture: the CPU and MMU are cycle-approximate, but the peripherals leverage modern host OS capabilities for better utility.

5. The Runtime Environment

Finally, we must look at how the emulator interacts with the host. The application is built using Swift and SwiftUI, utilizing the MVVM (Model-View-ViewModel) pattern.

The data flow follows a strict loop driven by a timer in the Motherboard class:

- Clock Tick: Fires at approximately 100Hz.

- CPU Burst: The CPU executes a batch of instructions (e.g., 5,000) to simulate real-time speed.

- Peripheral Update: Timers and UARTs are stepped forward based on cycles consumed.

- I/O Check: The UI renders output from the ASCI buffers and injects keystrokes into the input buffers.

This implementation avoids the complexity of multithreading locks by keeping the execution loop on the main runloop, which is an acceptable trade-off for a text-based OS emulator.

Conclusion

By studying the Retro180Emulator, we observe that computer architecture is not just about raw silicon; it is about the logical contracts between subsystems. Through the Z180’s banking mechanisms, the dispatcher’s I/O routing, and the interpreter’s fetch-decode loop, we see a complete, functional model of computation.